Continuation of the Smoke Jumper's story.

It was clear that the white people of Umitalla County were not used to seeing many black faces in their midst. Clearly there would be few of the joys of the black service clubs and homes of Atlanta and Fayeteville. A few of the troopers would find black girlfriends. Some of the officers would finally be able to find passable living quarters in town where their families could come and join them. But these were few indeed.

Fire fighting, of course, was an entirely new experience. And it was in this field that a new training began on 22 May. Wills set up one of his brilliant training schedules. It was a three week program which included demolition training, tree climbing and techniques for descent, if we landed in a tree, handling fire-fighting equipment, jumping into pocket-sized drop zones studded with rocks and tree stumps, first aide training for injuries—particularly broken bones. Troopers learned to do the opposite of many things they learned and used in normal--jumps like deliberately landing in trees instead of avoiding them.

Troopers would jump with full gear, including fifty feet of nylon rope for use in lowering themselves when they landed in a tree. Their steel helmets were replaced with football helmets with wire mesh face protectors. Covering their jumpsuits and/or standard army fatigues, they wore the air corps fleece-lined flying jacket and trousers. Gloves were standard equipment but not worn when jumping; bare hands manipulate shroud lines better.

Naturally their physical training program was intensified because missions often found troopers miles from civilization and in heavily wooded and mountainous terrain. It paid off handsomely in that few injuries occurred and only one death. On most of their missions troopers would work with forest rangers. The forest rangers could walk up the hills like a cat on a snake walk. They taught the tough paratroopers how to climb, use an ax and what vegetation to eat. At the time, troopers underwent an orientation program with forest service maps.

On 8 June, specially selected men began work with bomb disposal units of the Ninth Army Service Command, learning the business of handling unexploded bombs.

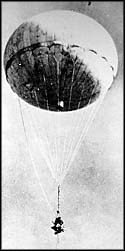

Then came new parachute. The parachute training was under a civilian, Frank Derry, who had designed the special chute for jumping in heavily forested areas. A special feature of the "Derry chute" was its maneuverability. By pulling the white shroud line the chutist could turn himself into a 360 degree circling movement. This, in turn, gave him a wider choice of landing areas - a vital factor when trying to avoid tangles with the highest trees in the thickly-timbered areas.

The chute training included three jumps, two in clearings and one in the heavy forest. The C-47 pilots who carried the 555th were a friendly, gung-ho lot, many of them were veterans recently back from flying "the hump" in Southeast Asia. Their spirit and were a welcome relief from that which we encountered among most other whites in the area. Whenever a trooper was injured, the pilots often beat us to the hospital to see how the injured smoke jumper was doing. One group of smoke jumpers will never forget the pilot who brought them all home in one trip, when a rule-book flier might have made at least two trips.

By mid-July, the entire battalion had qualified as "Smoke Jumpers"-- the Army's first and only airborne firefighters. Soon their operations would range over at least seven western states, and in a few instances, southern Canada. And there would be two home bases - one in Pendleton, Oregon and one in Northern California at the Chico Air Base.

By mid-July, the entire battalion had qualified as "Smoke Jumpers"-- the Army's first and only airborne firefighters. Soon their operations would range over at least seven western states, and in a few instances, southern Canada. And there would be two home bases - one in Pendleton, Oregon and one in Northern California at the Chico Air Base.

The main group would be bbased at pendleton, with the mission of fighting fires and handleing bombs in Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Idaho. Another group of six officers and nenety-four men would be based at Chico, to provide coverage for California.

FIRST FIRE CALL

The first fire call came in mid-July 1945 to suppress a blaze in Klamath National Forest in northern California. Between 14 and 18 July, the Chico contingent supplied fifty-six men. It was a successful mission with no injuries.

The first call for the Pendleton contingent come just a few days later on 20 July—to drop fifty-three men and two officers to fight a fire in the Meadow Lake National Forest in Idaho. The group took off at dawn in three planes, arrived over the drop zone (DZ) at 0830 hrs. Flying in trail formation, each plane made a low level (200 feet) pass over the fire area, looking for an acceptable DZ.

"After checking the wind by watching the smoke from the fire", Captain Biggs recalls, "the pilot and I made the decision on a one thousand foot drop—this was two hundred feet below the standard drop altitude. Swinging around to take advantage of the wind, the pilot gave me the green light and held the plane in a slow jump-attitude until I chose to jump. Once out, I did not manipulate or "slip" my chute—I just floated down like a wind dummy."

Meanwhile, the aircraft flew a 360-degree turn with the pilot and jumpmaster keeping their eyes on Capt. Biggs descent trajectory to see if he had made a timely exit; that is jumped at the correct landmark in order to land on the DZ without steering the chute. When he landed in the center of the DX, the pilot and the jumpmaster had their points of reference to follow. While they were trained to handle themselves if they landed in trees, most of the members chose clearings from force of habit and past experience.

During the initial pass of each C-47, an A5 container was dropped. The A5 contained axes, food, water, medical supplies and radio gear. This equipment was sufficient to sustain the group until they linked up with the forestry department personnel.

From 14 July to 6 October, the Chico and Pendleton units participated in thirty-six fire missions with individual jumps totaling twelve hundred. There were also casualties. In six months, more than thirty men suffered injuries from cuts and bruises to broken limbs and crushed chests. One typical report listed under "injuries": "1 EM (enlisted man) broken leg above knee, 1 EM knee out of place, 1 EM crushed chest."

On one jump in early August, one of the men suffered a spinal fracture. He remained on the scene throughout the fire fighting operation. Then, realizing his men were tired and short of food and water, he refused to burden them with the job of carrying him to the nearest airstrip. Somehow he managed to stand up and without help, walked straight-backed for eighteen miles to the strip where his units would be picked up by C-47 for the return trip to Pendleton. He spent weeks in the Walla Walla Hospital. Pure Guts!

Tragically, one man lost his life. The ill-fated trooper had landed in the top of a tall tree. In attempting to climb out his harness and lower himself with a rope that each man carried, he apparently slipped or lost his grip and crashed into a rock bed 150 feet below. It took three days for patrols to find his body.

Capt. Biggs recalls, "that all was not work. On 4 July we staged demonstration jumps for the local populace. We saw the famous Pendleton Rodeo. Killer Kane and I learned to fly from two grand guys, Pat Stubbs and Farley Stewart. We went to movies and took time to hunt and fish. I spent my spare bucks flying and seeing the west. We had storytelling sessions nightly at the BOQ. And we found the black WAC Company at Walla Walla Air Base happy to visit us (and our accommodations). Meanwhile, Graphite was serving as battalion taxi, cargo vehicle, and most loaned-out vehicle for anyone needing a ride to town.

For the first time in the annals of military history of any nation, a military organization of paratroopers was selected to become "Airborne Firefighters". The Triple Nickles became not only the first military fire fighting unit in the world, but pioneered methods of combating forest fires that are still in use today.

The conduct of The Triple Nickles during the heretofore highly secret and untold story contributed immeasurably to the well-being of most Japanese Americans in internment camps. If it were known that the Japanese balloons, the first unmanned intercontinental ballistic missiles, had been successful in reaching our shores, the Japanese military machine would have strengthened its efforts in that area. If the secrecy of the 555th’s operation had been broken, there is no telling what additional maltreatment would have befallen the incarcerated Japanese in western camps.

In October 1945, the battalion was assigned to the 27th Headquarters and Headquarters Special Troops, First Army, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In December, it was attached to the13th Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, where it proceeded to discharge "high point" personnel.

In February 1946, after two months of no supervision and watching friends leave for home, the 555th was relieved from attachment to the 13th Airborne Division and attached to the 82nd Airborne Division for administration, training, and supply. It retained its own authority to discipline and manage its own personnel matters. Further attachment was made to the 504th Airborne Infantry Regiment, then commanded by a colonel whose name will go down in history as the originator of "search and destroy missions" in Vietnam. General William C. Westmoreland.

As an integral part of the 82nd Airborne, the finest American division of World War II and commanded then Major General James M. Gavin, a man who unlike so many white commanders, was color-blind, 555th went on to become the first in many key areas of military innovations. Pioneering in integrating the Army was not the least among them, an action that changed forever the character of the Army and the nation. Today it is an acceptable fact that this pioneering by the 555th created the modem Army of today. And further, this achievement spread into all sectors of society. For original Smoke Jumpers it is gratifying to know than many of the techniques and equipment tested and developed during "Operation Firefly" are still in use in both civilian and military fire fighting missions.

Traditional wisdom conveys to us that past events and history carry the portents and guidance for the future. Dismissing that antiquated notion, these black soldiers relied on human perceptions of the known conduct of black military men in the familiar hostile white environment both military and civilian. There was not a necessity to try to philosophize, theorize and intellectualize their role and contribution. Theirs was a new phenomenon to all walks of American society and the meaning of the experience of pioneering in becoming the first military "Smoke Jumpers" in the world. They shunted the windows of the past and dominated this scene by values of character, drive, pride and unity.

Copyright © 1996 Patrick O'Donnell